“Look at a page of the score and list everything you see.’ It’s right before your eyes.”

When I was a college student, my piano teacher told me that score study was an important part of practising. I didn’t think of asking him how to do it. I just took my score of Beethoven Opus 7 and walked it over to the couch. I stared at it for a while, but that was about as far as I got. But the truth is, I did want a deeper understanding of music. I had recently heard the late Schubert sonatas for the first time, and I wanted to take them apart and look for what I now call ‘the magic’: the compositional elements that give a piece its identity. Although I was taking analysis classes, I was still just collecting tools and terminology. I had not yet found an approach that I could make my own. I realize now that what I was looking for was a way of integrating score study with those great listening experiences. I wanted to use my emotional reaction to the music as a place to begin analytical thinking.

Decades later, I have come up with my own methods of getting inside the score to get closer to the music. I call them ‘easy entrances to the score’. These techniques have completely revolutionised the way I teach and practise.

First, I use what I call The Three-Step Method. For each passage I ask three questions:

- Step 1: What is the character?

- Step 2: What in the score creates that character?

- Step 3: What does this imply for my interpretation?

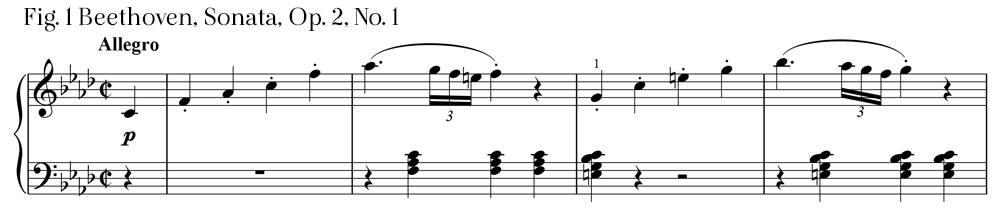

These three steps provide a smooth entrance into the score. Let’s try this method with the opening of Beethoven’s Sonata Opus 2, No.1.

Step 1: What is the character?

The answer to this question is brief and subjective. We don’t think much. We use only our initial reaction to the music. For me, nervous energy comes to mind.

Step 2: How does Beethoven create this character?

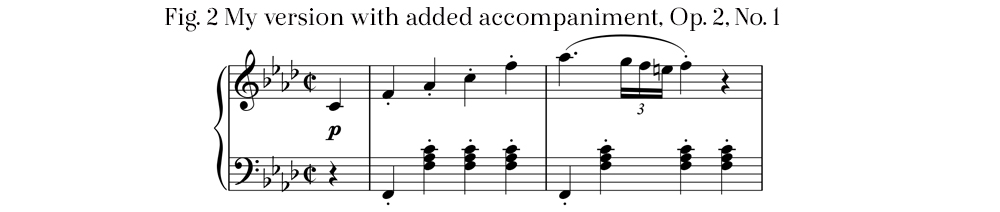

This second step is no longer subjective; it is time for fact-finding in the score. The very opening measures have energy because of the charging ‘rocket’ motive and the fast triplets; but what I find more interesting is that the nervousness comes from the absence of accompaniment, as well as the delay of a strong downbeat. The meter is not established until the downbeat of bar 3. Of course, for some of us the piece is so familiar that we are not actually confused when we listen to it. But imagine Beethoven’s audience hearing it for the first time; the very first note could sound like the downbeat. I suggest comparing Beethoven’s opening to the following version to which I have added a simple accompaniment:

In my version there is no doubt about the meter. Comparing these two versions helps me to appreciate the uncertainty of Beethoven’s opening. Although the opening arpeggiated ‘rocket’ motive was a common musical tradition of the day, a rocket motive was usually supported by a strong downbeat, as in Beethoven’s Opus 10, No.1, for example:

Both opening themes feature rockets, but Opus 2, No. 1 sounds more agitated, while Opus 10, No. 1 is more declamatory, largely due to this rhythmic difference.

Step 3: What does this imply for interpretation?

The answers here are once again subjective, but based on observations from step 2.

To bring out the uncertainty in bars 1-4, it is crucial to avoid accenting the first downbeat, so as to keep the meter a secret. To emphasise the first clear downbeat (bar3), we can crescendo with the left hand chords, which will sound agitated in contrast to the natural tapering of the melody in bar 2. We should also make only enough crescendo in the first rocket as is necessary for shaping, in order to stay in the uncertain character.

I studied this piece as a student but never thought about the absence of bass at the opening. I also never considered that the unpredictability of the rhythm was crucial to the identity of this theme. I probably just focused on articulation and dynamics without going deeper into the score to find out what was really going on. But now, having this method, I am challenged to think about more than just musical gestures and traditions; I now know that there are ways to get in touch with why I love the music.

Here is another way into the score that I find extremely useful: I call it The Surprises Method. The idea is to identify all the unpredictable moments in a piece and ask, ‘What is the effect of this surprise on the listener, and what does the listener expect instead?’ This technique is especially useful for well-known pieces that don’t surprise us anymore. It is often the unpredictable moments in music that are the most deeply affecting.

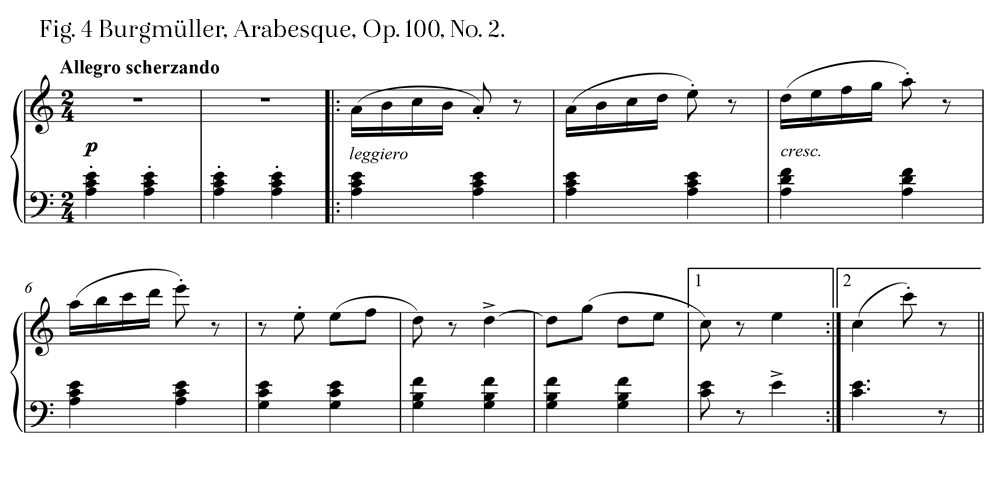

Let’s try The Surprises Method with Burgmuller’s Arabesque, Opus 100, No. 2. So many students play this piece! It is masterfully crafted, and much more appealing than a typical etude, largely due to its surprises. We will focus on the opening section, although the surprises continue throughout the piece.

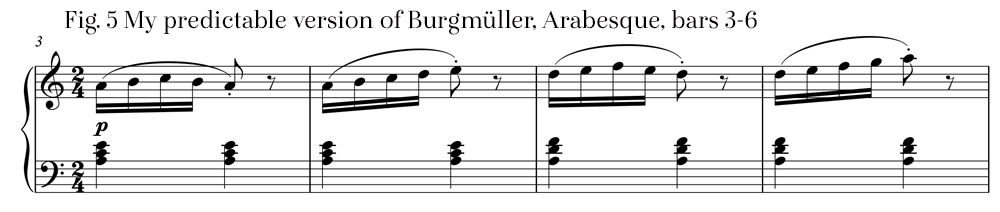

The first surprise happens in measure 5: the melodic pattern skips the material we expect. Instead of continuing the pattern predictably…

Burgmuller skips ahead:

By skipping material, Burgmuller creates a sense of rushing to the top of the phrase. For performance then, I suggest opening the piece with a very strict tempo, and then in bars 5 and 6 moving the phrase forward to show the accelerated material.

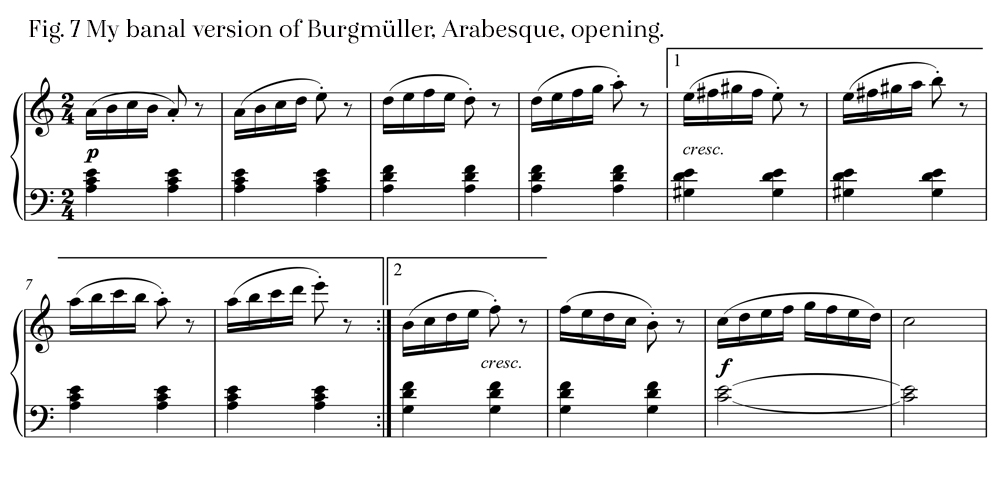

The next surprise happens in measure 7. Suddenly the theme becomes lyrical and moves abruptly to C Major. The way the piece begins, with the scherzando quality of the runs, we don’t expect this opening phrase group to end so lyrically. Imagine this piece as a simpler, more banal etude:

I encourage my students to make a big deal out of the surprising change in m.7. I even suggest adding touches of pedal there to show the shift to a sweeter mood. I also recommend taking a little time on the downbeat of measure 7 to emphasise the sudden changes.

Whether we are teaching a Beethoven Sonata or an intermediate piece like the Burgmuller, we need to base our interpretive decisions on the score for the most convincing performance. Even beginners can enjoy studying the score. They always like to be asked questions like, ‘Why do you think the composer called this piece Dreamy Clouds?’ When they answer that the notes are high up and that it moves slowly, they are already engaging in score study!

The Three Step Method and The Surprises Method are only two of many ways into a score. The key is to choose a starting place, such as your favourite moment of a piece. And if in doubt, I like to follow the advice of my former teacher, Gyorgy Sebok who said, ‘Look at a page of the score and list everything you see.’ It’s right before your eyes.

Want to read more from Ruth Price?

Right Before Your Eyes passionately delves into piano music through score study, based on the idea that if we start with our emotional reactions to the music, analysis and interpretation will flow more naturally.

Buy from your preferred retailer or online here