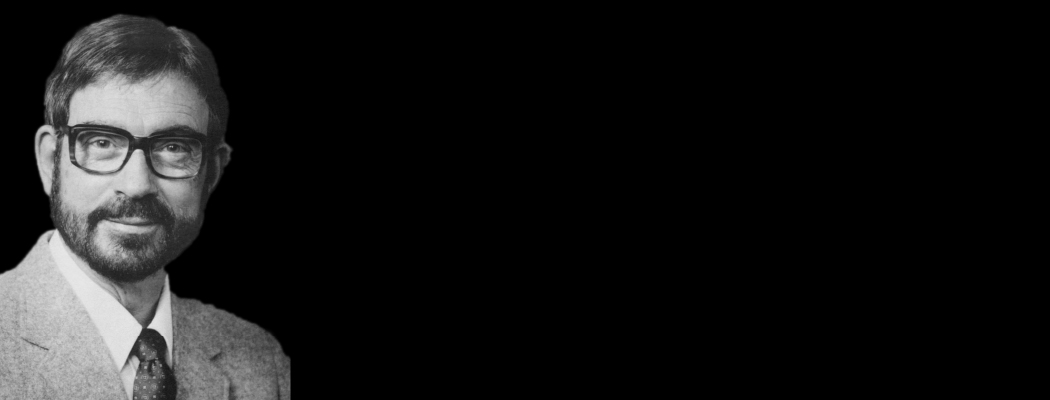

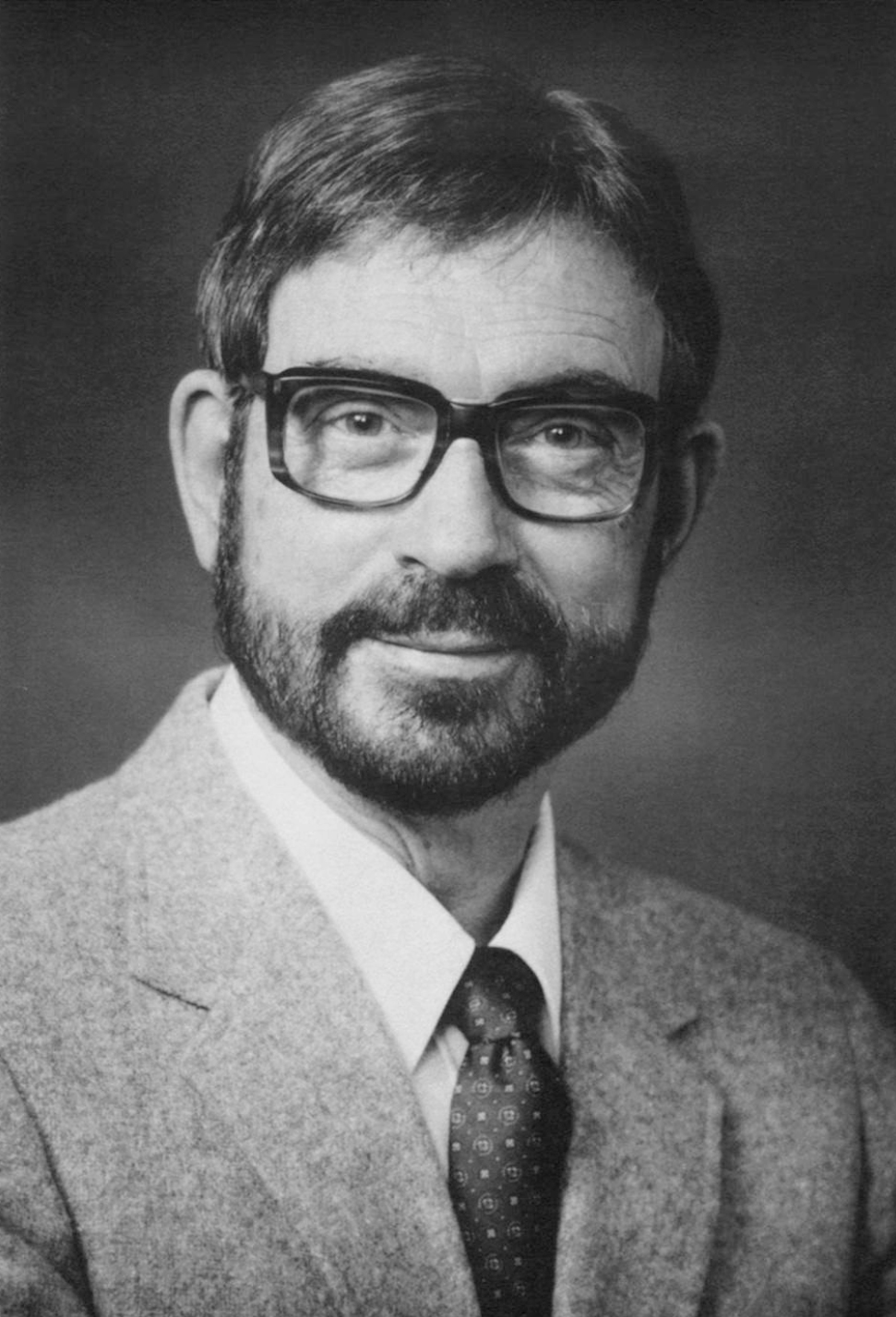

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of William Gillock (1917–1993). Few composers have impacted students and piano teachers across the globe as much as Gillock did. Almost 25 years after his passing, his compositions are still in wide use today, appearing on state and national repertoire lists across the country, exam syllabi and in Japan, where he is beloved, to name a few. The late Lynn Freeman Olson observed “the Gillock name spells magic to teachers around the world,” and Martha Hilley of the University of Texas wrote in her article about Gillock, published in 1993: “Teachers knew there was no question of whether to purchase his music; they simply bought it, took it home, and taught it; and student interest and success were almost assured.”1

What was true then, still rings true today. Gillock’s music simply has the ingredients of being instantly appealing and musically gratifying for the student. What greater legacy could any pedagogical composer desire? But that isn’t where Gillock’s appeal or legacy ends. He was equally renowned for his astute abilities as an adjudicator and for the hundreds of inspirational workshops he gave for Willis Music Company. For those who knew him personally, he was cherished for who he was as a person as much as he was for his music.

Without exception, everyone with whom I’ve had a conversation about William Gillock describes him as the gentlest person you would ever want to meet, and said he made you feel as if you were the most important person in the room. Glenda Austin, whom he mentored as a young teacher, described him as being patient, generous, charismatic and kind. Others said he was inquisitive, intelligent, humble, even self-deprecating and never one to put on airs. In my personal view, he was always a gentleman, elegant and refined. He took time to linger, whether it was with you or in his music, and wanted you to share in the beauty of whatever commanded his attention.

“How many times have pieces from the three volumes of New Orleans Jazz Styles, Carnival in Rio, Holiday in Spain, his Lyric Preludes, among a multitude of others, made the difference between students stopping lessons or inspiring them to reach for greater musical heights?”

I met William Gillock in the fall of 1983. I was 26, and my career in the retail print music industry was just beginning. He had agreed to let me interview him for our store newsletter, and I remember feeling nervous because he was the first “famous” person in the piano teaching world I had ever met. We sat down to have lunch and within minutes he put me completely at ease; his charm cast a spell over me.

He actually touched my life long before our first meeting. I started piano lessons the summer I turned 10 years old, and the first piece of his that I ever played was Aeolian Harp. Instinctively, I perceived something different about this piece from music I had played before. There was fluidity and a sense of spianato. Of course, my musical sensibilities were just beginning to take shape, but even then I felt a sense of completion and inevitability in those final eight measures. I didn’t have the musical vocabulary to articulate what I felt, but the natural flow of the musical line moving from one hand to the next and the innate musicality of his phrases lured me into wanting to play Aeolian Harp as beautifully as it deserved. It changed how I wanted to play the piano.

There is no doubt in my mind that what I felt has been replayed over and over in the hearts of literally tens of thousands of students and teachers. My experience with his music is the perfect example of what Gillock strived to do with every composition he created. He wanted every piece to inspire the student. He wrote this in a letter to Dallas teacher Becky Corley in 1979:

I believe that more students have learned to play well because of exciting literature than for all other reasons combined. If a piece seems worth the effort of learning, the student is more likely to give willingly—even enthusiastically—the time and thought necessary for a beautiful performance.2

If you have taught his music, it is quite likely that at one time or another, a Gillock piece has inspired one of your students to play beautifully and exceed their own expectations. How many times have pieces from the three volumes of New Orleans Jazz Styles, Carnival in Rio, Holiday in Spain, his Lyric Preludes, among a multitude of others, made the difference between students stopping lessons or inspiring them to reach for greater musical heights?

William Gillock was born on July 1, 1917, on a farm in Lawrence County, Missouri. His father Claude, a dentist in the small town of La Russell, loved music and learned to play several instruments by ear. His mother Gertrude was a housewife, and raised William and his younger brother, Robert. He grew up in a time “when 150 buggies came into town on Saturday. There were three drugstores, three doctors, a bank, hardware stores, grocery stores, and feed stores. It was at the tail end of an era when small towns served an important function because there were no rail systems connecting one large town to another.”3

At age 3, Gillock began picking out melodies and harmonising at the piano; and at age 6, he began lessons with a teacher from Carthage, another small town 15 miles away. Like many students who are blessed and cursed with the ability to play by ear, his playing far exceeded his ability to read music. About his lessons he said, “I’m not sure you would call it study; she taught me more or less by rote. After many years, I had learned to play some pieces, including the C-sharp minor and G minor preludes of Rachmaninov… when she assigned me a piece in six sharps, I didn’t read it; she played it for me and I took it home and figured out what sounded good. I suppose she did the best she could.”4

When he attended Central Methodist College in Fayette, Gillock majored in art and not in music. Given his musical background, the college could not accept him as a piano major without requiring him to take remedial music courses first. Still, music was his first love and during the last two years of college, he took informal piano and composition lessons from Louise Wright, a teacher and published composer of children’s literature. She immediately recognised Gillock’s natural ear for improvisation and she encouraged him to compose music for students.

Under her supervision he learned music theory and notation, and eventually he submitted 30 pieces to G. Schirmer, out of which five were chosen for publication. He was paid $10 outright for each composition. “That was enough to buy at least 20 pairs of shoes!” he said.5

His early compositions displayed a natural talent for composing and a knack for student pieces in particular. As a teacher, he knew the importance of writing music that fits the hand, and he always composed with an ear toward making the music sound harder than it was to play. Perhaps his most defining characteristic was his uncanny ability to write in any style. His compositions were so true to the period that if you didn’t know the piece, it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference between Gillock and a so-called “real” classical composer.

His ability to capture different styles was directly related to his ability to empathise, and he found inspiration from watching movies, absorbing the culture of what he saw and felt, and translating it to the music he composed. When he wrote Carnival in Rio or Holiday in Spain or On a Paris Boulevard, he had not yet traveled to those countries, but he managed to capture the character and essence of each one as if he had.

His inspiration to compose came from many sources, but most often he simply sat down with the idea to write music. When I asked him about his process, he said that to compose he had to have the feeling of “absolute and infinite leisure.” He was also quoted as saying that his process was far more intuitive than intellectual.6 Many times he finished a piece and put it aside, only to return to it later. He played it over and over again making sure there was nothing awkward in it. If he felt pressured or hurried in some way the music just didn’t come out. The feeling of “infinite leisure” was central to his creative process and helped him achieve a state of “flow,” a concept that noted psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi used in his research on creativity. If that is true, the stars must have been perfectly aligned when he composed Fountain in the Rain, his best-selling composition. Austin asked him how long it took him to write it, and with a snap of his fingers he said, “Just like that. I just sat down and it came out.”7

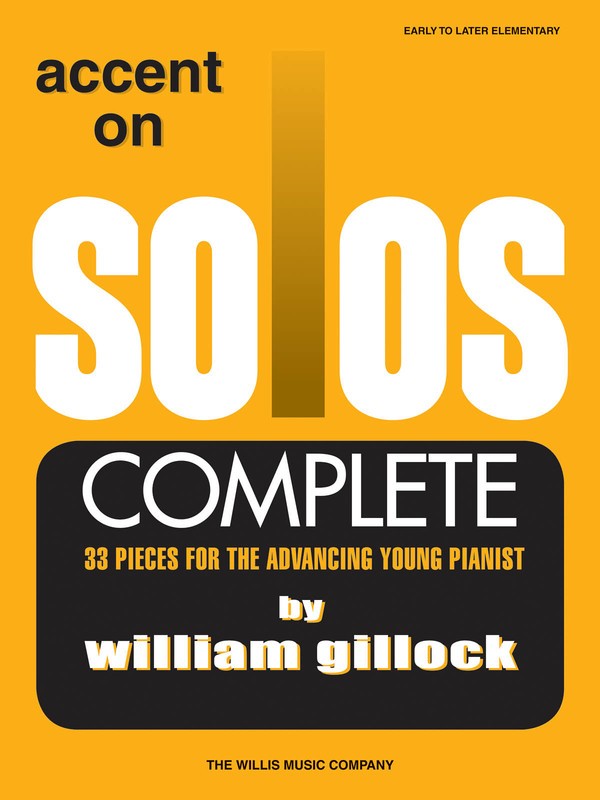

Despite his gifts, Gillock struggled early on with the inordinate amount of time he spent on notation. Before entering into his first royalty agreement with Boston Music, and later an exclusive contract with Willis Music, he sold many (not all) of his pieces outright and felt it was hardly worth the effort he spent on the manuscript. When he moved to New Orleans after college, he made a living by playing gigs and teaching lessons, and he didn’t compose for the seven-year period from 1946–1953. However, in the years that followed, from 1956–1969, he experienced an extremely productive period. He wrote several singles that are still favorites today: Sonatina in Classic Style, Portrait in Paris, Sonatine, Flamenco, Three Jazz Preludes and others. His collections during this time included the Accent On series, the three New Orleans Jazz collections and the development of his Piano All the Way method.

Even at the height of his popularity as a composer, Gillock maintained his sincere humility. Possibly he was self-conscious about his lack of formal training, or maybe it was just plain good manners that motivated him to say of himself, “I’m just a mildly talented composer who had the good fortune to compose the right things at the right time.”8 He also said “The success I’ve had with most of my grading may be due to the fact that I am a pianist of meager means. I have always said, if I can play the piece, surely any reasonably well-coordinated pupil can also play it—often better than the composer.”9

Gillock is proof positive that talent, genius, and the preternatural creative urge must and will emerge regardless of any obstacles. Every teacher knows all too well that talent alone is not enough, and in this regard, Gillock had the wherewithal to actually learn enough to be able to express the music that was within him. He was constantly asking questions and enlisting the help of trusted friends who guided him. When you consider that his early music training was spotty at best, that he didn’t really read music or understand how to count sixteenth notes until

he was in college, and that he never took a formal course in composition, these impediments are nowhere to be heard in his compositions. His music is unmistakable in its ability to inspire and touch the hearts of students and teachers. In the words of Dallas teacher, Trudy Emerick, “That was the magic of William Gillock.”10

One can argue that his music transcends the misnomer of being called teaching literature; it simply stands on its own as literature with which we teach the piano. At the very least, his music is timeless, and several new editions now feature updated titles that reflect our changing world, but the music remains the same. These distinctions are some of the many reasons his music is revered and why it is still so popular today.

For all that William Gillock achieved, his kindness and unwavering desire to encourage people was at the heart of who he was. His genuine interest in his friends and in the teachers he met across the country and the world touched us in small and profound ways. This is perhaps best personified in two people who have worked tirelessly to preserve the longevity of Gillock’s music: Hiroko Yasuda and Henry Doskey.

Yasuda, a teacher and founder of the Gillock Association in Japan, had a long and lovely friendship with him. “He taught me many things,” she said, “not only about music, but also about life and how we should be as human beings. From him, I learned what music is, and he completely changed my musical life.”11 Yasuda was so inspired by him that she founded the Gillock Association to share his music and philosophy with other teachers in Japan. She was also instrumental in making his music available in Japan, where it enjoys a passionate following.12

Doskey, who has recorded the complete piano music of Gillock and given many workshops on his music, began his piano studies with him in the 1950s in New Orleans. He remembers Gillock’s kindness as the trait that most influenced him: “I find on reflection that much of what I am as a teacher and musician I owe to his example of calmness, gentleness and professionalism, as well as the good basics I learned in his studio. I especially strive to emulate his positive and cheerful attitude in my dealings with my students.”13

Those who knew Gillock best found it difficult to separate the man from his music, and maybe that is as it should be. “He was an encourager. He wanted to help you be better,” Emerick said. “His giving spirit is best characterized in a poem that he discovered and came to love”:

Choose something like a star;

A course, a dream, a thing of beauty,

Or the tiniest bit of the distant

Improbable grandeur of the vast

Gray space of likelihood.

Let it lure you and lead you

From the dismal doom of fact,

The dark and dreary world of is.

For whoever is dream-possessed,

Though his reach must exceed his grasp,

Is borne by winds of ought to be Into the now of eternity.

Author Unknown14

As we celebrate the centennial of his birth, I want to leave you with a final personal story. During my career in the retail print music business, I had the privilege of working with David Karp in putting on the National Piano Teachers Institute at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Each year we invited several clinicians to present workshops and master classes during the week-long event. In 1987, William Gillock participated in the Institute for the first time. Coincidentally, I turned 30 years old on the first day of the Institute.

Unknown to me and in an act of infinite kindness, Karp asked all of the clinicians to compose a birthday song in my honor. Each was performed for me on the first morning of the Institute, and I will never forget William Gillock’s eloquent arrangement of Happy Birthday. Last year, it was published by Willis Music, and it is fitting that we should remember him with his own arrangement of Happy Birthday (available from www.halleonard.com.au).

So, happy birthday to you, Bill; may your music live forever, and may the magical joy that it has brought to thousands of teachers and students outlive us all!

Notes

1. Martha Hilley, “The Last Interview with William Gillock,” Clavier, 1993.

2. William Gillock, Letter to Becky Corley, 1979.

3. Hilley, “The Last Interview with William Gillock,” Clavier, 1993.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Gillock, Letter to Becky Corley, 1979.

7. Interview with Glenda Austin October 2016.

8. Hilley, “The Last Interview with William Gillock,” Clavier, 1993.

9. Gillock, Letter to Becky Corley, 1979.

10. Interview with Trudy Emerick 2016.

11. Email correspondence with Hiroko Yasuda, October 2016.

12. Phone interview with Charmaine Siagian, Hal Leonard Corp., October 2016

13. Kathryn Starnes Duarte, The Piano Music of William Gillock; Doctorate Dissertation 2004

14. Interview with Trudy Emerick, October, 2016.

This article was originally published in the February/March 2017 edition of the American Music Teacher (a publication produced by MTNA). http://www.mtna.org