A series of professional development workshops held across Victoria by the AMEB

When I was first approached about these workshops, I put a question on a Facebook page for Australasian piano teachers — ‘If the AMEB were to run workshops on Piano for Leisure, what would you want to cover?’ The answers came in from teachers: how to deal with the rhythms in the popular and jazz repertoire.

Armed with an array of percussion instruments, I am now travelling to regional Victoria and centres in metropolitan Melbourne, involving the teachers and their students in getting the feel for the rhythms that underlie these works, with a particular focus on the pieces in the AMEB publications in Series Two and Three of Piano for Leisure. While Series One is still deservedly popular, I thought that it has been well understood by this stage.

Often I say to students ‘Play as if there is a drummer playing with you.’ And no, the metronome alone is not enough. Ensemble instrument players learn quite early that the music goes on in time — if they miss a note or think they need more time to prepare, that can only be done in solo practice. Pianists are often alone for so much of their learning that the continuity of the music doesn’t always develop for a student. This need not be, ensemble experience can be part of piano lessons too. A few percussion instruments in the studio, a second keyboard, a few shared minutes with another student, or playing with the teacher’s accompaniment and so much of the style and feel can be developed in the student’s performance. This is not for the metronomic effect alone, but as a contributor to an understanding of style.

The idea that all music is based either on song or dance has been an evergreen starting point for discussion. I think I first heard Bernstein make that pronouncement. Dance rhythms are abundant in the classical piano syllabus too, but as those pieces are all original works composed for piano, the rhythms are frequently somewhat stylised. To a dancer though, for example, a minuet played at a different tempo from the one danced is simply not a minuet — regardless of the composer’s intention for the composition.

Piano for Leisure of course contains a rich variety of arrangements of music from many genres, and we might expect a great aural familiarity with the original source materials. The pieces are driven by implied dance styles and so these rhythms are frequently more explicit in presentation in these works. There can be challenges in representing these on the piano. There are many subtleties of touch to be engaged for these pieces to be satisfactory in performance, and for the students’ full enjoyment.

With this thought in mind I sought to organise the dance styles in the Piano for Leisure repertoire into families of style. From the boogie and blues through bounce, swing, shuffle, and rock to the Latin groupings — samba, bossa nova, rumba, and tango groupings. Then there are the pop songs where the influences of these styles come through in the accompaniments.

The next task I set for myself was to check the editorial and composers’ given tempo on each piece. I played all of the Series Two and Three pieces faster, slower, and at the given tempo, sometimes back and forth for six or seven performances for some pieces. I noted the tempi as I went. I came to the conclusion that for almost all of the pieces, the given tempo really is the optimum for a stylish performance. In the case of some of the boogie and blues pieces, especially at the lower levels, there was considerable leeway in the tempi before the styles were compromised, but in the main the printed tempo was spot on. One piece that might appear somewhat compromised is Billy Joel’s Root Beer Rag — an enjoyable marathon of running semiquavers at a suggested 130–136 bpm in the Piano for Leisure Series 3 Grade 7 book. I clocked Joel’s performance at 168 bpm, but it’s still possible to have a lively performance at the more achievable tempo suggested for a grade seven student.

The fact is that the tempi of many of the pieces exceeds the level of technique that would be acquired if the student only practiced the set technical work for each level up to the minimum speeds. This of course is a point that I make in teaching the classical syllabus too — if a student aspires to certain repertoire, then the technical work needs to be adjusted to slightly exceed the demands of those pieces.

In reviewing the works I did find myself in conflict with some pedaling in a few of the jazz pieces. I’d be inclined to reduce it greatly, and in some cases have no pedaling at all. To many jazz pianists, the only time to pedal at all is during a ballad.

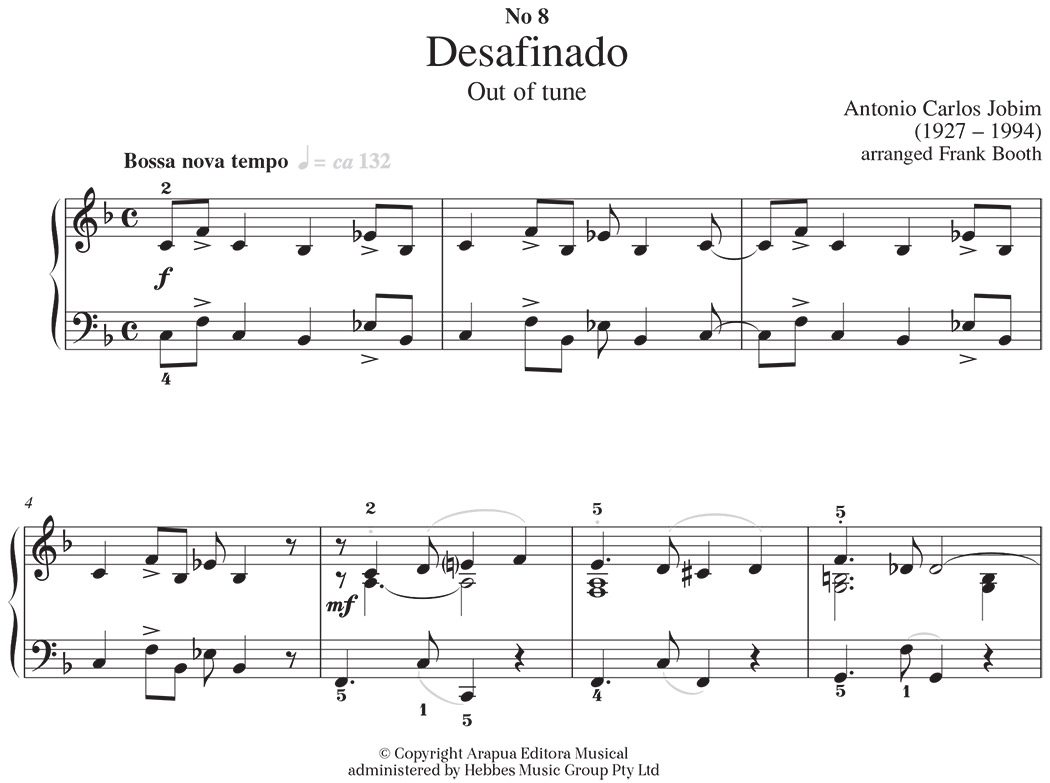

I also looked at articulations, and there again are both composer/arranger and editorial suggestions. There are detailed dots, dashes, accents, and slurs — regard the example above, an excerpt from Frank Booth’s arrangement of AC Jobim’s Desafinado, from the Piano for Leisure Series Two Grade Five book. The arrangement shows a montuno introduction, then the pianist must play with three differing layers of dynamic and articulation: a gently detached singing melody, a soft sustained accompaniment, and a bass line with a bass player’s non-legato touch.

It would be possible to follow those instructions carefully, but not achieve a stylish performance. This is of course the nature of all music notation, not a fault of the example at all, but exactly how to touch and articulate becomes immediately apparent to the player when surrounded by the percussion that sets the style.

At the workshops, both teachers and students have learned to play rhythm patterns on various percussion instruments as a path to appreciating these subtleties of style. They played them as ensembles for pieces of a range of the above mentioned styles selected from the Piano for Leisure books. It was such a delight to hear a student at a recent seminar adjust the degree of articulation in response to the aural cues from the percussion patterns I had taught the group of teachers at a recent workshop. We had listened to the original 1963 Getz/Gilberto recording, learned the rhythm patterns, and created an ensemble that then stimulated the student’s excellent listening skill to produce a very stylish performance. The ensemble taught the articulation.

Many of the jazz pieces demand a non-legato touch. In this, these works have much more in common with baroque articulation than with classical or romantic piano music. We deal with the question of ‘just how staccato is that note to be?’ Again, this was much easier to demonstrate with our teachers’ percussion ensemble setting the style. There are also the perennial questions of whether to swing the quavers or not, how much to swing, and why in some music we swing the semiquavers instead!

We listened to Stéphane Grappelli to demonstrate how to be lyrical, yet rhythmically precise against a swing backing, we heard Sarah Vaughan’s swing treatment of Shearing’s Lullaby of Birdland. We listened to Ute Lemper’s extremely personal and at times wild interpretation of Monk’s Round Midnight, listening to where on the recap she imitated inflections from the saxophone solo, and mused on how it related to ornamentation in a da capo aria. We also noted how sometimes a guitarist, pianist, or bass player in these arrangements would substitute a chord — sometimes more than occasionally. All of this is marvellous for sharpening the aural skills, as well as stimulating the imagination.

Teachers and students participating together to create music, enhance its enjoyment, and increase the depth of understanding of style. This has been the product of the AMEB’s It’s all in the Rhythm workshops.

On reflection, I realise in my career as a performer and teacher I owe a huge debt to many mentors, but for this project two come to mind. Two people who influenced my teaching, and whose ideas underlie what has been presented at these seminars. The late and wonderful Nehama Patkin, who taught me to look for the dance rhythms in the music and make them explicit, and Lois Singer, who always exhorted us to limit the use of discussion in teaching, and ‘use music to teach music.’