[dropcap letter=”I”]t seems counter intuitive that the goal of the successful piano teacher is to ultimately make themselves redundant. The successful teacher equips the student to become an independent learner, able to listen, read, interpret, play and perform.

To that end students come in a wide range of ages and stages of development, with varied needs, expectations and ambitions and piano teachers require a vast array of strategies, repertoire, learning experiences and teaching styles to accommodate and motivate their students.

Some students learn piano because they love music, some so as to develop their sight-reading skills while others want to play by ear and resist learning to read. Students may learn piano as a first step to another instrument, or due to parental request. Some want to perform as much as possible, while others are timid performers who are anxious playing in front of other people. There are students who are preparing for auditions, completing formal exams and some aiming to become professional musicians. Others learn to play for pleasure and fun with them, music making is a relaxation or escape.

Regardless of the reasons why a student learns piano, everyone enjoys playing something familiar. The request to learn the current pop songs, jazz pieces, and or film themes is a universal experience for piano teachers, and students who only wish to learn songs they “know” can be the most challenging to motivate and teach. Popular and jazz pieces are often complicated to read, demand a sophisticated skill set, and once learned may not sound as the student expects. How does the piano teacher meet all these varied motivations and aspirations and still include relevant technical work to develop the musician?

A fabulous personal discovery that has inspired and encouraged every student in my studio is the incorporation of aural (music without notated scores), and creative tasks as a part of the practice routine. Music is first and foremost auditory, but so often we start with the visual, which is the printed music, then introduce the sound. Perhaps the desire to establish regular “practice” routines early in the learning process results in printed music being sent home for practice from the beginning lessons. Most piano teachers use and follow tutor books and time honoured methods of teaching which are rooted in reading the music then playing, but there are other practice tasks that can be set for student practice that do not require printed music. Practice that includes repetition of creative auditory exercises will offer the student a feeling of achievement and success, provide a kinetic vocabulary, lay down an auditory library of sounds and make practice addictive.

My incorporation of improvised, creative and aural based exercises as part of the weekly lesson and home practice, resulted from both the imperative to foreground new pieces so that when the student came to learn the piece, the tune was familiar; and observations that students were often able to execute new (sometimes complex) co-ordination tasks without looking at the music but stumbled when trying to both read the musical symbols and perform the skill required. Planning ahead and foregrounding the learning of a new rhythm, pitch pattern, skill or technique to be encountered in the student’s next piece solved this issue. Once students mastered the new skill set; for example a new rhythm or fingering of a new pattern, the written symbol is shown and associated with the sound and skill already acquired. This approach prevented a cognitive overload where the “eye” interfered with the hearing and performance of the new skill. One example of the process of using aural memory and improvisation to teach the new skill is outlined below.

Case Study: Jessica

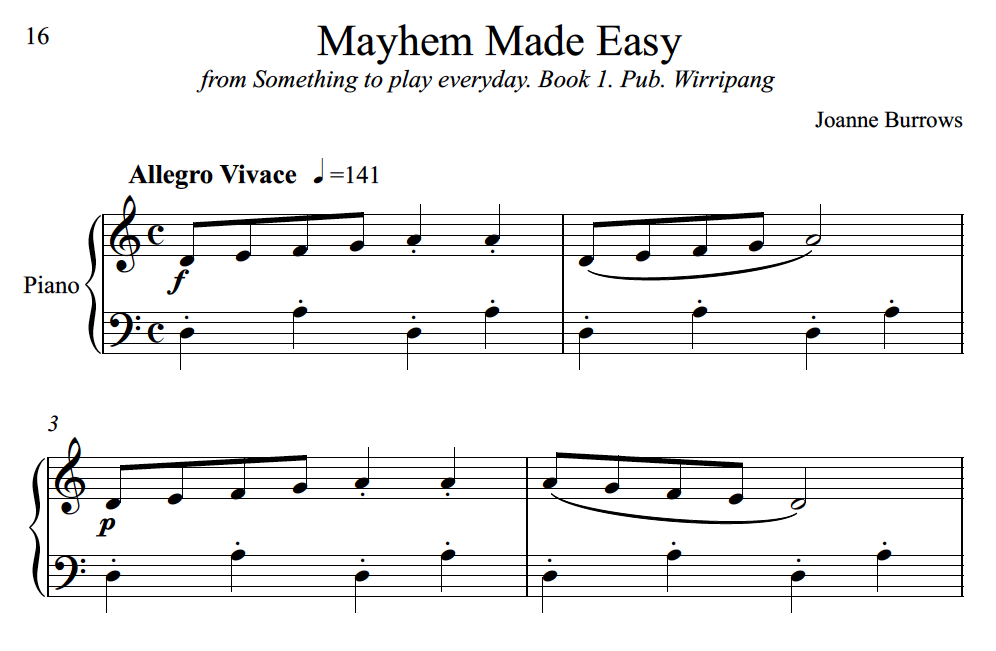

Example 1: Mayhem Made Easy

This is Jessica’s new piece. Before I show her the printed music I consider what she already knows and has played in previous pieces. She knows:

- D position,

- Five finger stepping patterns,

- Staccato and legato.

But she has never had to play an ostinato in the left hand against a different right hand pattern or rhythm.

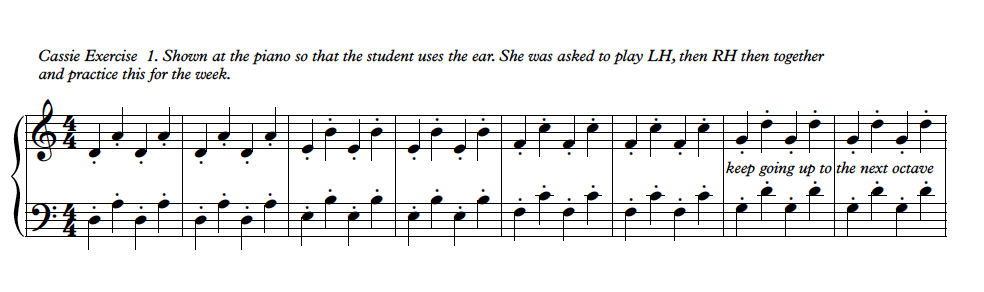

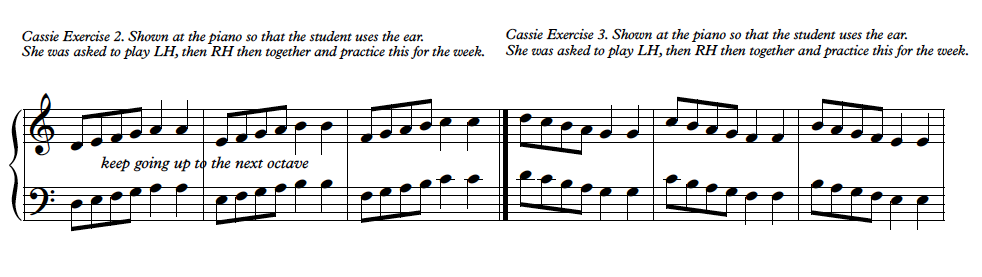

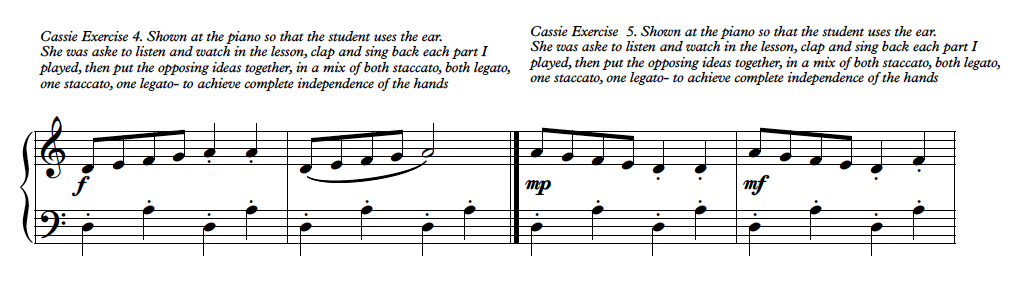

Using aural and creative tasks as a prelude to showing Jessica the music provided her with the kinetic and auditory skills to successfully read, memorise and play her new piece within a few minutes of seeing the printed music. First I clapped various rhythms for her to echo. Second I sang bits of the tune and bass for her to sing with me. Next I played Jessica the various exercises for her to copy, and practice at home, I did not show her the music. Once she was finding the first exercise easy, I introduced the next ones and Jessica practised the exercises as part of her weekly warm up. (Please note, different students will accomplish the tasks at different rates, some will be able to master all the exercises in one or two lessons others may take several lessons, but do not show them the printed music until the physical and aural aspects are secure.)

This process uses improvisation, (the student is free to play around and create their own ideas from each exercise), develops the ear, the fingers and the co-ordination. As the student is moving around the different positions on the piano, the teacher may also discuss, major, minor tonality, transposition, harmonisation, and other compositional devices. For example: try the passages hands together in contrary motion.

Once Jessica had mastered all the exercises to acquire the relevant kinetic and aural vocabulary, I showed her the printed music, explaining the symbols and asking questions. LH bar one is the ostinato- where else is it in the music? What chords does the ostinato use? RH Bar one is the five finger pattern, where else is it in the music? Does it always use D position? Jessica was able to read the piece through and memorise it within a week. Overall, using this method, the time it took for her to learn the piece hands together, to a performance standard was halved compared to previous time frames. I also made sure I followed up the acquisition of the new skills and concepts with a few sight- reading examples and performance pieces that used similar patterns to those encountered in Mayhem Made Easy, then expanded the repertoire out to include similar patterns in different keys and positions

Exercises that are learnt aurally and memorised in the lesson, practiced and used for improvisation at home, before introducing the notation proved effective for beginning and intermediate students. The student was able to build on their prior learning when shown the new written symbols and match the new to what they have experienced and performed. Teaching the skill, internalising the physicality of the movements, then later showing the visual symbols also prevents many rhythmic errors from developing during the learning process. Deconstructing a new skill and rebuilding it “aurally” (without using the printed music) allows the student the freedom to acquire the skills without the eye “getting” in the way.

Five Routines based on making music that foster student progress and motivation:

All tasks are taught and practiced “by ear”, without the student looking at any printed music until after the skill or skills are acquired.

- In the lessons: Echo clap the rhythm; use a pattern from one of the student’s repertoire, and or unknown patterns and new patterns from the next piece set for study. Set some tapping and counting aloud tasks.

- In the lessons : Play the rhythm pattern on a single note of student’s choice, an octave higher, an octave lower, over a scale. Use Left hand, Right hand, and hands together.

- In the lessons and at home: Play the pattern on one triad, two different triads, or a progression used in one work from the student’s repertoire, or a progression created by the student.

- In the lessons and at home: Play the new idea or pattern using different rhythm patterns, (for example, all dotted, all semiquavers, all minims) then transpose this, use a sequence, (it may be from the student’s repertoire).

- In the lessons and at home: Add suitable chords to a right hand pattern or exercise. Combine two of the above ideas or make up a new idea.

A few creative tasks set each week can achieve fantastic outcomes across all aspects of music learning, including confidence, memory development, understanding of form, harmony and melody line, co-ordination and development of new skills and finger dexterity. Using the ear, creative practice and improvisation in combination with reading notes has motivated my students to practice at home and improved their listening and reading skills.

Presented at the 12th Australasian Piano Pedagogy Conference, Melbourne 2015

[separator type=”thin”]

Joanne Burrows is a passionate educator, and in pursuit of this calling she has been very successful in writing music education compositions for Australia publisher, Wirripang. She is the Head of Piano & Music Craft Riverina Conservatorium of Music and is undertaking her masters at CQU- Central Queensland University in music education.

Reference List and Further Reading

BJ Wadsworth. Piaget’s theory of cognitive and affective development: Foundations of constructivism . White Plains, NY, England. 1996.

KW Fischer. A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review, Vol 87(6), Nov 1980, 477-531.1980.

Margaret S. Barrett. A Cultural Psychology of Music Education. Oxford University Press. 2011.

Choksy, Lois . The Kodály Context: Creating an Environment for Musical Learning. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. 1981.

Orff, C. & Keetman, G. English Version adapted by Margaret Murray. Orff- Schulwerk. Music for Children.Music for Children. Vol. 1. Pentatonic. London: Schott, 1957.