Serving Up the Skills to Get Your Head in the ‘Game’

I first encountered The Inner Game of Tennis when it appeared on the reading list for one of my piano teaching courses at university. Needless to say, I was curious how forehands, backhands and volleys would be relevant to my musical education. But after tracking down a copy for myself, I discovered that The Inner Game of Tennis is not just for Federer fanatics. The book serves as a guide to the mental side of peak performance, with strategies to improve concentration, perseverance and emotional control from the perspective of renowned sports psychologist W. Timothy Gallwey.

So how is this information relevant for musicians?

In Chapter One, Gallwey lists some common problems that many tennis players — both amateur and professional — encounter on the court:

I play better in practise that during the match.

I know exactly what I’m doing wrong on my forehand, I just can’t seem to break the habit.

Every time I get near match point against a good player, I get so nervous I lose my concentration.

I’m my own worst enemy; I usually beat myself.

And I couldn’t help but notice a few similarities to what I hear as a music teacher:

My piece always sounds better at home!

I know I’m playing a wrong note, but I just can’t seem to break the habit.

I get so nervous when I perform that I lose concentration and then I make a mistake.

I’m not good enough to perform in front of other people.

Musicians need to know how to overcome nerves, negativity and self-doubt just as athletes do. Many of us underestimate the importance of mental toughness and the part it plays when we practise and perform. It appears that we could learn a thing or two from our tennis counterparts, so here are a few key points that stood out as I read The Inner Game of Tennis…

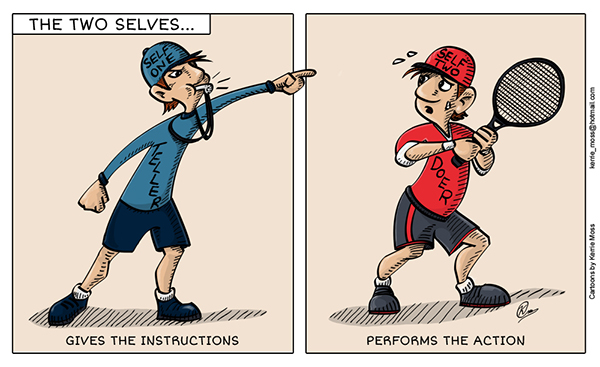

The Two Selves

I’m not afraid of anyone, but sometimes I’m afraid of myself.

— Justine Henin, former world number one tennis player & winner of seven Grand Slam singles titles.

We’ve all seen the way that tennis players communicate with themselves on the court. Whether it’s a high-pitched shriek from Sharapova, a pumped up ‘COME ON!’ from Hewitt or some racquet slamming from Serena, we all wonder what goes on inside the mind of a player during a match. In the quote above, Justine Henin admits that it’s not her opponent she fears on the court, but rather how her own thoughts, criticism and self-doubt can affect her during a match. According to The Inner Game of Tennis, we each have two selves. Self 1, known as the teller, gives the instructions and Self 2, the doer, performs the action.

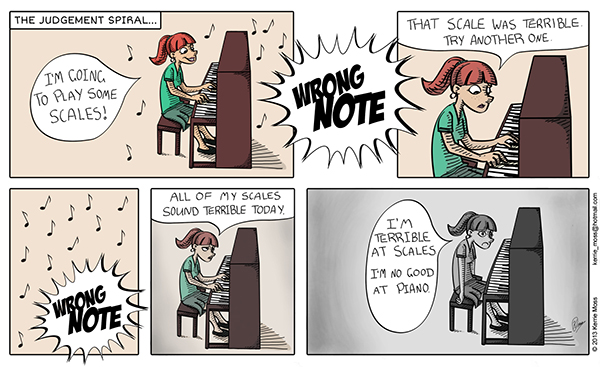

Self One is our ego mind. He cares about our self-worth, our self-esteem and how we appear to other people. Self Two controls our nervous system, which in turn helps all parts of the body to communicate with each other. More often than not when something isn’t going our way at the piano, Self One is quick to criticise. He starts to lose trust in Self Two (our natural ability) and fills our head with negative thoughts — I can’t play this piece! This is too hard! I keep making stupid mistakes! When we hear these comments often enough, we start to believe them. Before we even sit down at the piano, we expect that what we are about to play won’t be any good. Instead of making harsh judgements and getting fixated on what we did wrong, we should look to find the source of our mistake and focus on how to fix it. Acknowledging mistakes allows us to improve and get better, as opposed to dissolving into a negative thought spiral or completely ignoring the mistake. According to composer, professional performer and piano teacher Elissa Milne, a huge percentage of our ‘mistakes’ at the piano are the result of unsuitable fingering. Keep hitting a wrong note? Struggling to play a passage legato? Locking in secure fingering will always help to facilitate a confident performance.

There are many other possible reasons why we make mistakes (two of which will be discussed further in this article), but it is important to remember that there is often a reasonable solution. Taking the time to find the cause of the error (in piano practice as in life) allows you to make a good decision as to how to create effective change*.

Instruction Overload: Less is More

The dumber you are on the court, the better you are going to play.

— Jim Courier, former world number one tennis player and winner of four Grand Slam singles titles.

Another speed-bump on the road to successfully conquering our ‘inner game’ is over-instruction. Whilst we shouldn’t take Jim Courier’s advice too literally, it is important not to become weighed down by continuous thoughts. Quite often when we are performing — either during our lesson, at home or on stage — Self One gives us a running commentary of things to remember — Remember the tempo is slow here, slow down, don’t make a mistake in that bit, keep the tempo steady, did I play that right? Don’t play loud, take the pedal off here, play smoothly, remember the G# here! G#! G#! — and the list goes on. These non-stop verbal commands are not only distracting, but they interfere with our creativity and the expressive qualities of the music, as Gallwey explains:

All this internal conversation actually triggers a stress system that causes you to tighten both physically and mentally, and go into a reaction that’s not creative…where you don’t trust yourself to respond to the reality of what’s going on.

Instead of incessantly commenting on the music line-by-line, bar-by-bar, note-by-note, we should have a vision of what our performance should and could be. A ‘game plan’ if you will; for musicians, this is best achieved by thinking less and listening more:

Images are better than words, showing is better than telling, and too much instruction is worse than none.

When trying to see the ‘big picture’ of a piece of music, it is imperative to listen to recordings. Hearing a finished, polished recording of the piece will be much more inspiring than just looking at notes on the page. And don’t stop at just one — listen to as many recordings as possible to find inspiration for how you want to play the piece, and then put your own creative spin on it afterwards. Recording yourself playing your pieces is also extremely beneficial as it gives you the opportunity to hear and/or see things that you may not normally notice.

Concentration: Learning to Focus

I just try to concentrate on concentrating.

— Martina Navratilova, former world number one tennis player and winner of 18 Grand Slam singles titles.

Any time we sit down at the piano to practise, our head can be overflowing with several different thoughts — not all related to piano — that distract us from what we initially set out to accomplish. Gallwey believes that the art of concentration is crucial to our inner game. It allows Self One to quieten down and Self Two to be in control. In order to maintain concentration and stop our minds from racing away, we have to focus our attention in the present moment:

Focus of attention in the present moment is at the heart of doing anything well…The greatest lapses in concentration come when we allow our minds to project what is about to happen or to dwell on what has happened already.

When we let our minds race away with ‘what if’s’ and ‘maybes’ we start to get swept up in an imaginary reality — What if I make a mistake at Bar 72? Then I’ll lose my place and I won’t know how to keep going and then I’ll stop in the middle of my piece in front of everyone! Before you know it, you are barely aware of what you’re playing and panic mode ensues. So how do we achieve focus? Focus does not mean staring hard at something, and it only becomes more difficult when we try to force it. Natural focus occurs when the mind is interested in what we are doing. Here are a few ways to help keep our mind focused when we perform.

Before You Perform

To keep nerves at bay before you get up on stage, it helps to focus on your breathing. As Gallwey states ‘Breathing is a very basic rhythm. When the mind is fastened to the rhythm of breathing, it tends to become absorbed and calm. Place your mind on your breathing process’. Also, if you are using music, have the music open and imagine playing the piece through in your head.

On Stage

Before you start the piece it helps to hear the first bar in your head so you can imagine how you want the note to sound. It also gives you that sense of rhythm right from the beginning of the performance. Also, position your body so that you are balanced and comfortable as soon as you sit at the piano. If you are moving or shuffling around on the seat and your feet are not stable, you will be very distracted and your technique will suffer as a result.

While You Perform

Focusing on the rhythm of a piece of music can help musicians to maintain concentration and keep our full attention in the present moment. Concentrating on the sense of rhythm gives our mind somewhere to focus and stops it from rushing away with worried or panicked thoughts. Having this type of focus is how we become a consistent performer.

Final Thoughts

Focus of attention in the present moment is at the heart of doing anything well. Focus means not dwelling on the past, either on mistakes or glories; it means not being so caught up in the future, either its fears or its dreams, that my full attention is taken away from the present. The ability to focus the mind is the ability to not let it run away with you. It does not mean not to think — but to be the one who directs your own thinking.**

*(Milne, E., Piano Lessons for Life: Don’t Correct Mistakes, elissamilne.wordpress.com) **(Gallwey, W. T., The Inner Game of Tennis, pg. 131) ILLUSTRATIONS BY KERRIE MOSS (kerrie_moss@hotmail.com)