[separator type=”thick”]

Among the list of objectives in the AMEB piano syllabus levels 1 and 2 are the following:

~ Rhythmic and metric stability

~ Articulation of legato, non-legato and staccato textures as required

~ Musical phrasing and punctuation

As an examiner and teacher I find these aspects are often lacking in control, so much so that I published a text on the subject! – Rhythm Unravelled.

[separator type=”thick”]

Rhythm

In Rhythm Unravelled rhythm is defined as ‘the arranging of notes (and rests) into musical ideas or phrases’.

These phrases range from simple to complex and students need to be taught from the beginning to be fluent in reading them. This process is ongoing – teachers can’t afford to let up for a moment. Pianists especially are often deficient – generally unable to benefit from playing in ensembles.

“counting is the easiest way, it’s universal, and if the facility is developed from the first lessons will lead to an understanding of rhythmic patterns and a secure sense of pulse and beat”

Some teachers, and even teaching systems, do not advocate counting – often more of a ‘feel it’ approach. I find this perplexing, frustrating and daunting when facing a new or referred student who, many in upper grades, haven’t a clue how to figure out the most straight-forward passage.

Apart from anything else – counting is the easiest way, it’s universal, and if the facility is developed from the first lessons will lead to an understanding of rhythmic patterns and a secure sense of pulse and beat – an inherent sense of rhythm. Then the ‘feel it’ factor will kick in, allowing a slackening off of the actual counting process. (I still count in tricky passages).

Counting must be smooth and perfectly even and needs extensive practice on it’s own to develop fluency with the syllables. If rhythm is isolated, meticulous attention can be paid to metrical note/rest values to develop absolute security – which carries over into other aspects of technique; it works wonders for sight-reading!

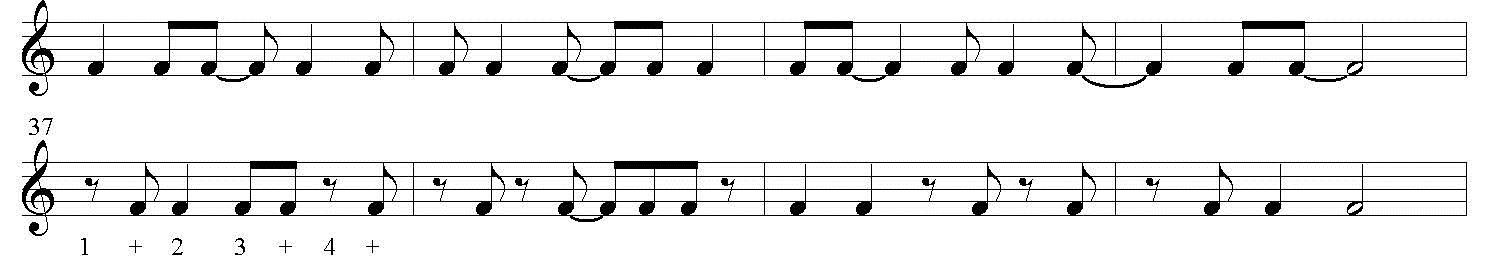

Rhythm Unravelled commences with simple whole, half and quarter note/rest exercises, gradually introducing eighths and more syncopated patterns so that by Ex.10 the following should be easily clapped/played:

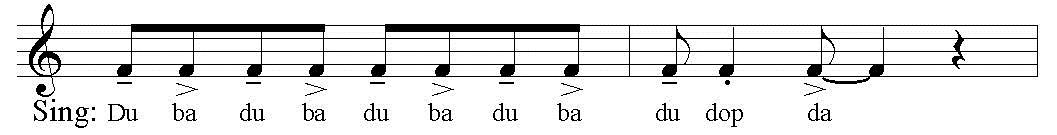

Chapter 3 introduces 1/16ths and leads to mastery of the following more complex syncopation:

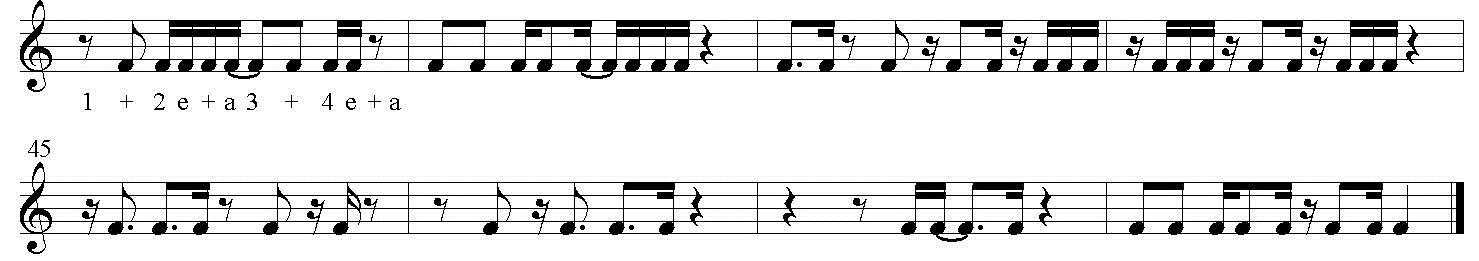

Compound time is introduced in chapter 5 Ex. 22. For swing jazz a facility with triplets is vital for the swing pulse to be internalised, enabling focus on the music itself:

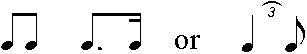

For classical pianists swing quaver (1/8th) notation can be confusing:

Often these different pairs can occur in the same bar, especially the first two.

The rule is: count

as

Practise this counting until secure.

The rhythmic phrases above should be a breeze for students from about grade 4-5.

Articulation

The first step for legato is ‘clear, even articulation of the notes’ (syllabus objective for technical). This of course requires ‘systematic fingering’ (I pencil it in) and ‘controlled co-ordination of the hands’. Non-legato is more problematic; just how long should a shorter note be? Students need guidance here and with experience will acquire the facility for subtle gradations – also with staccato.

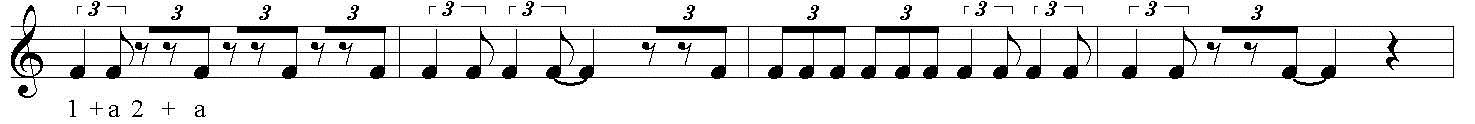

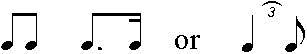

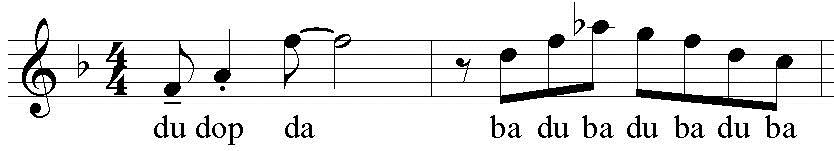

I recommend singing phrases to better assimilate articulation (and phrasing) and in the Rhythm Unravelled section on this subject I give examples of ‘scat’ syllables which can be employed for this purpose:

[separator type=”thin”]

The (slight) accent on the off-beat ba here is for jazz styles; for classical no accent but the same or similar syllables; e.g. da va. (Listen to: The Swingle Singers sing Bach or Mozart; Bobby McFerrin sing Bach – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hg3IhpT6_8w). For triplets – da da ka.

Combined with counting, this system has lots of advantages: e.g. a legato/staccato pair; and a phrase commencing on an up-beat:

In my opinion music with a judicious use of legato, non-legato and staccato textures is wonderful for developing security of touch, tone etc. If candidates present an exam program demonstrating fluency in each the examiner is sure to be more impressed!

Phrasing

Have you noticed that all of the above examples (including the rhythm ones) consist of one or two bar musical phrases – some extending into four bars?

In Rhythm Unravelled a phrase is defined as ‘a passage of notes (and rests) forming a musical idea; often indicated by a slur.’ Phrasing is often used to describe the playing of as little as a pair of notes, perhaps the du dop da in the example above. This could be a half-phrase – in fact this whole line (bars 9-12) could be considered as one phrase, despite the rests and legato/staccato articulation.

For a clear example of phrasing see Triplet Falls p.16 in the last issue (four) of this magazine. The dynamics here will especially help the student to shape the phrase – a short crescendo sweep up to the climactic note, then a more gradual dim. to the end note.

Practice

Much of my time with students is taken up with teaching them how to learn/practice – this doesn’t appear to be taught in schools? The main focus is on the repetition of a phrase, perhaps units as small as motifs or sub-phrases. Every aspect – fingering, rhythm, articulation, dynamics etc. – needs to be learned and perfected from the beginning. A practised mistake is extremely difficult and time-consuming to undo. Remember – practice makes permanent.

One thing which needs to be eradicated (preferably never started) is stopping for minor slips – even major ones when a piece has been learnt. This can become a habit. I recommend practising playing through slips – a facility which could come in handy in the heat of an exam – and will also assist sight-reading.

Listening

‘How do you expect young people today to learn good manners when they never see any?’: Fred Astaire.

A similar question may be asked of music; how many students presenting for piano lessons have ever heard fine classical or jazz recordings – let alone live performances?

A regular portion of my lessons is spent with students listening to and comparing recordings; e.g. checking how professionals shape a particular phrase, what articulation, dynamics, tempi etc. An excellent source is the AMEB Recording and Handbooks – also containing analyses.

For jazz and popular styles an invaluable practice tool is listening to and playing along with backing tracks. All my publications are available with CD containing a demonstration and backing tracks in several tempos. Rhythm Unravelled has a CD with backing tracks for all exercises. The AMEB CPM publications all have accompanying CDs. For pianists especially – the benefits of playing with backing tracks are numerous: example, motivation, rhythmic accuracy, sense of beat and timing, momentum, ensemble experience, balance, sight-reading and perhaps most of all – enjoyment!

I wholeheartedly agree with Elissa Milne on the subject of repertoire and endorse the 40 Piece Challenge. I expect my students to learn most if not all the pieces in any album they possess – especially the easier ones – and quickly! Something I haven’t promoted enough is the fact that all my albums – despite the pieces being spread over a few grades of difficulty – are designed as suites, so they may be played as a set – so there’s a challenge!

In conclusion – perhaps we teachers need to check the Syllabus objectives of levels 1-3 regularly for pointers on how to better equip our students for examinations – and who knows which one may develop the ability and artistry to one day grace the concert platform.